The Persistent Gender Pay Gap in Academia

Policy Brief by Anita Pahangdar, the IgniteHER Policy Team

The gender pay gap, referring to the difference in the average earnings between men and women has always been a problem, but while it may not always receive immediate attention, the gender pay gap represents a significant issue with far-reaching societal implications. This problem arises for various reasons and could affect many different systems greatly, one being the education system, which has been neglected for too long.

The issue is rooted in similar issues: underrepresentation, systematic barriers, pay discrimination, and institutional biases yet as you dive deeper into the problem, many additional factors play a role.5,11,13 The gender pay gap carries significant societal consequences aside from gender inequity: financial distress, reduced retirement income, and broader economic impacts and its importance lies in its ability to stem from seemingly small disparities that escalate into larger systemic challenges.

Statistics from 2024 reveal that, on average, women in full-time jobs earn 93% of what men earn in the United Kingdom and 84% in the United States and Canada. Although these rates don’t appear alarming, we have to understand that the educational system's unique dynamics are essential to addressing the gender pay gap, as it affects not only educators but also the students they shape and the future workforce they influence.

Extensive research has examined the issue's roots and effects, often compared to other systemic inequalities. However, this study takes a different approach by investigating the structural inequalities that contribute to the gap itself and many small reasons that have been overlooked for too long.

This research will explore the underlying causes of the gender pay gap within the education system, examine its implications on equity and quality, and propose actionable solutions to address and prevent these disparities. Despite its far-reaching impact, this issue has been largely neglected within the system, with insufficient attention or action to address it. More advocacy is crucial to bridge this gap, like the efforts we undertake at IgniteHER to amplify women's voices and push for equitable reforms. Addressing these inequalities requires targeted strategies that reduce but ultimately prevent their occurrence, ensuring a fairer and more inclusive educational landscape.

Methodology

To analyze the persistent gender pay gap in academia, this research combines qualitative and quantitative approaches, aiming to uncover key contributing factors and their underlying causes, which make the issue particularly difficult to address. Each phase of the methodology is carefully structured to provide a thorough and nuanced understanding of the problem, laying a solid foundation for developing effective and actionable solutions.

Overview of Key Findings

Over time, numerous research studies have been conducted to explore the root causes of the gender pay gap, offering valuable insights into the factors that sustain this inequality. By analyzing findings from studies conducted in 2004, 2012, and 2021, this section aims to trace the evolution of these causes and assess whether societal progress has contributed to narrowing the gap or, in some cases, exacerbating it.

This chronological approach allows a deeper understanding of how economic, social, and institutional changes have shaped the issue over nearly two decades, providing a clearer picture of persistent challenges and emerging trends. By structuring the analysis, we can identify patterns and shifts that may inform more effective strategies for addressing the pay gap in academia and beyond.

In 2004, Donna K. Ginther, and Shulamit Kahn explored the economic structures and systematic barriers contributing to gender inequality in academia in their paper "Women in Economics: Moving Up or Falling Off the Academic Ladder?" Their research primarily addressed occupational segregation, highlighting that fewer women are represented in high-paying roles. They also analyzed the barriers women face in achieving tenure and leadership positions, emphasizing the structural challenges embedded in the system.

Christine Doucet, in 2012, shifted the focus to the education system with her research "Pay Structure, Female Representation and the Gender Pay Gap among University Professors." Doucet examined the influence of pay structures on gender inequities, identifying systemic practices such as market supplements that perpetuate disparities. Similar to Ginther and Kahn, Doucet also highlighted the underrepresentation of women in leadership roles, particularly in academia, where women are less likely to hold senior positions.

Finally, Ariane Hegewisch and Eve Mefferd provided a broader perspective in their paper "The Gender Wage Gap by Occupation, Race, and Ethnicity." Published in 2021, their research delved into the systemic causes of the gender wage gap across various industries. Hegewisch and Mefferd shed light on biases in hiring and promotion, the undervaluation of professions dominated by women, and the intersectional disparities that compound wage inequities for women of different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

From these studies, we can draw a clear outline of the key factors contributing to the gender pay gap.

Traditional norms and patriarchal systems, which historically expect women to prioritize domestic roles, have created a structure where men dominate high-paying jobs. This entrenched system perpetuates a cycle that is difficult to break. Women are often deprioritized in hiring and promotion decisions due to biases, such as the perception that they are more likely to take maternity leave or paid time off. In corporate settings, these ingrained norms further widen the pay gap, as women lose opportunities for equal pay and advancement in a system designed to favor male-dominated career trajectories.

Quantitative Analysis

Starting with the K-12 education sector, Hegewisch's research highlights a persistent wage gap even in professions dominated by women. In 2020, elementary and middle school teachers, who are 79.3% female, earned only 86.2% of what their male counterparts earned. Similarly, among teaching assistants, women made 82.5% of men's earnings, despite representing 82.8% of the workforce.

As the level of occupation and responsibility increases, the pay gap widens significantly. Chen's research at Ohio State University revealed that women earned, on average, 21.4% less than men across all academic ranks. Among clinical faculty, controlling for rank and department reduced the gap from 11% to 2.62%, indicating that biases tied to rank and departmental structures play a significant role. However, for non-clinical faculty, the disparities persisted, with women earning $28,000 to $32,000 less annually than men within the same rank.

Chen also highlighted that tenure achievements were notably skewed: 54% of men attained tenure compared to 41% of women in 2016. This disparity underscores the systemic barriers women face in advancing their academic careers.

Furthermore, Doucet's findings emphasized the inequitable distribution of "market supplements," with women being nearly three times less likely than men to receive them, even when accounting for career stage and academic field. The introduction of Canada Research Chairs (CRCs) exacerbated these inequalities. With only 15%-18% of these lucrative positions awarded to women, the pay gap was widened significantly, as CRCs provided substantial pay supplements ranging from $30,000 to $40,000.

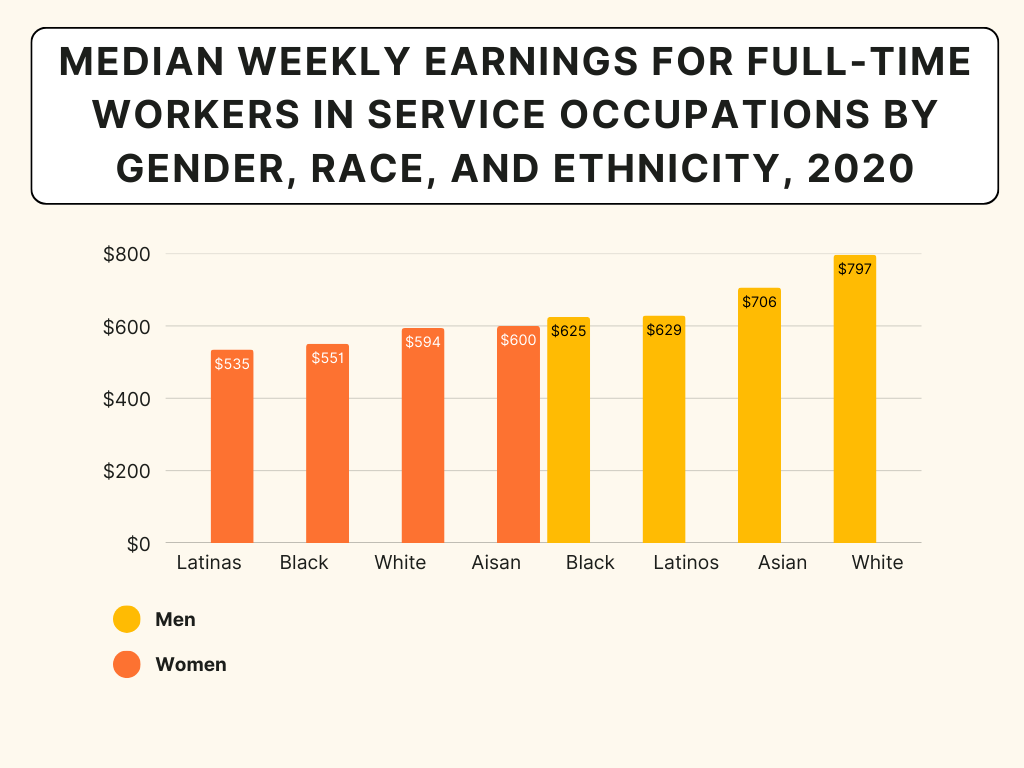

Lastly, Hegewisch's research extended to disparities across race and ethnicity, as shown in the graph below. The data demonstrates that even within the same occupation, women of color—such as Latinas and Black women—earn significantly less than their male counterparts, highlighting the intersection of gender and racial inequities in wage distribution.

Comparative Insights

Quantitative analysis data shows a disturbing consistency: systemic inequities, rooted in patriarchal norms and institutional biases, continue to disadvantage women at every level of the education system—from K-12 teaching roles to the highest ranks of academia—women consistently face barriers that limit their earning potential, career progression, and access to leadership positions.

These patterns reflect a system where, even in professions dominated by women, wage gaps are entrenched, signaling the undervaluation of "women's work." The disparities widen as roles become more specialized or carry greater responsibility, further marginalizing women. Structural factors, such as inequitable pay supplements and biased tenure processes, further amplify these inequities to make sure women experience not just a pay gap but also a "promotion gap."

Intersections of gender, especially with race and ethnicity, continue to cause deeper chasms. Women of color bear a disproportionate wage burden not only in comparison with male workers but also in comparison with white female workers—a fact that shows how injustices are perpetrated systemwide and inequity and underrepresentation for marginal groups are aggravated.

Overall, such findings underline both the omnipresence of a gender pay gap and the immediate need for intervention with a multi-faceted solution. Indeed, such problems require an approach that targets not only changes in institutions—including pay transparency, equitable promotions, and chances for leadership positions—but also brings about a kind of cultural shift to challenge just those societal norms that breed such inequities.

Discussion

Bringing together the data and research, it becomes clear that the effects of this unequal system are profound and far-reaching. When women are underpaid in professions where they are the majority, it perpetuates an ongoing cycle of bias and barriers. These barriers not only hinder women’s ability to succeed but also reinforce patriarchal systems and cultural norms that devalue their contributions.

What makes this particular issue so pernicious is that the impacts of inequality provide an active feedback loop to its causes. This systematic underpayment for women further implants and normalizes these inequalities at the individual levels. Beyond the individual effect, this portends wider ramifications, which affect not only educators but institutions and society generally.

In a system where women are paid less for doing the same tasks as men, the hidden message is that their work is less valued. The devaluation creates an environment of bias that indeed invalidates their efforts and diminishes their contribution. At this pace, such an environment will destroy workforce diversity, creating division and inequity. This indeed contributes over time to the marginalization of women in the workforce and limits their presence within leadership and decision-making structures.

In this case, such institutionalized disparities economically and socially act to reinforce systemic inequality. The failure to bridge pay gaps acts to perpetuate economic disparity and gender inequity by sustaining such structures. The effects will spill over to individual women and deleteriously affect the growth of healthy societal norms that support women's participation and advancement. The inequality spiral ensues, building a system more resistant to being addressed and torn down.

Recommendation

To address this global issue, we can draw inspiration from the policy approaches adopted by other countries, particularly the United Kingdom, Germany, and Northern Ireland. Research by Gamage, Cullen, and Jones highlights the effectiveness of three strategies in significantly reducing the gender pay gap: pay transparency policies, stronger institutional frameworks, and cultural and workforce adaptations.

Cullen’s research identifies three types of pay transparency with distinct impacts:

Horizontal Pay Transparency: This concept aims at reducing the pay gap between genders by forcing employers to publish pay grades across comparable jobs. For example, in Denmark, compulsory pay transparency forced wages 2.8% down for firms just above the size limit but firmed up for pay equity. But this would run the risk of shifting the bargaining power towards employers and could have wide-encompassing effects on overall wages.

Vertical Pay Transparency: Vertical pay transparency provides potential earnings through promotion opportunities that may be a motive for employees to strive harder and become more productive. Workers often underestimate how their career advancement will improve their finances; vertical transparency corrects the misconceptions that lead employees to exert more effort and ambition.

Cross-Firm Pay Transparency: This approach provides pay benchmarks among different firms, raises wages, and fosters competition among employers. For example, in Slovakia, the pay transparency law led to a 3% average wage increase after its implementation, thereby showing its potential to advance equity without lowering overall wages.

Pay transparency policies can help bring down disparities in pay, but at the same time, they are not implemented without their drawbacks. Horizontal and vertical pay transparency risks a generally lower level of wages due to changes in pay structures by employers. Nevertheless, cross-firm pay transparency provides probably the best hope for improvement in baseline wage hikes and fairness in wages, not dampening general pay levels.

The gender pay gap in NI is narrower than that in the rest of the UK. This can be attributed to higher educational attainment and professional occupational allocation among women, as well as a more compressed earnings distribution. The more compressed wage structure has contributed to reduced overall wage inequality and provides a model for fostering equitable pay systems.

It is important that academic unions are empowered to promote equitable pay policies and that gender equity audits form part of institutional reforms. Jones's research in Northern Ireland illustrates how good union representation contributed to the narrowing of pay gaps due to centralized wage-setting mechanisms. That shows how unions can become drivers of change toward systemic results, ensuring not only that equitable practices are implemented but also that they endure.

Apart from that, institutions should have strong support systems that include resources and training on how to manage salary and promotion negotiations for women. These would address the challenges that women face in negotiating compensation and career advancement opportunities on equal terms, hence closing the gap.

A key next step for the future will lie in the frequent implementation of gender equity audits to assess trends in pay gaps, representation, and promotion trends at academic institutions. The audit should not just highlight the differences but also form a basis on which clear and corrective measures can be made. Inclusion necessarily requires the use of an intersectional framework to make sure that ambulatory actions will address the compounded inequities faced by women of color, LGBTQ+, and other marginalized groups. This helps the institution further an inclusive and equitable environment.

By implementing these policies, we take another step toward creating a truly diverse, inclusive, and equitable workplace. These changes help in bringing even the smallest systematic disparities, such as pay transparency, nondiscriminatory promotion, and equal mentoring, that could provide a fertile ground for structural change upward.2,3,10,11 Aggregating these individual improvements dismantles deep-seated biases and discriminations to construct a level playing field where women do not face arbitrary obstacles to their success.

In addition, outreach and support should be specifically directed toward women of color to ensure that the solutions are intersectional and inclusive. Operating at the intersection of gender and racial biases, women of color often face compounded challenges that amplify their marginalization in the workforce. Institutions can make sure that no group is left behind by addressing these unique challenges through mentorship programs, career development resources, and fair hiring practices. These intersectional approaches go a long way in creating a culture of equity and inclusion, where no one, because of gender, race, or background, is deprived of an opportunity to succeed.

Call to Action

The gender pay gap in academia and overall has to be addressed with multilevel involvement. It is very much evident that those countries that have implemented policies of pay transparency, strengthening institutional frameworks, and fostering cultural and workforce adaptation, have indeed achieved progress that can be perceived by closing this gap. Drawing inspiration from these very successes, definite action needs to be taken in order to let the environment of equity be made available for one and all.

It will also be of importance if the policymakers can join in implementing full pay transparency legislation. Cross-firm pay transparency, similar to that done in Slovakia, has stood the test of time, raising the floors of wages as a proven model to create fairness. It is also important that regular gender equity audits be institutionalized for detecting structural disparities and instituting appropriate remedial policies. These will have to apply an intersectional framework to reduce these compounding inequities felt by women of color, LGBTQ+, and other marginalized groups.

These are changes that academia needs to make, starting with transparent pay structures and fair promotion. The institutions should also have well-established support systems for women, including mentorship programs, negotiation training, and leadership development initiatives, to remove barriers in their path. Let the institutions lead the way by taking priority measures toward inclusivity and equity.

Unions and activist groups have the power to implement systemic changes. The empowerment of unions to fight for pay policy equity and collective bargaining can institutionalize fairness. Such groups should elevate the voices of underrepresented groups to ensure that their distinct challenges are listened to.

Society as a whole must finally rise to the challenge of cultural mores that demean women's work and perpetuate systemic biases. A shift in perception, and inclusivity at all levels of government, institutions, and communities, provides the bedrock for real change.

It's time for action. With these evidence-informed strategies, combined with the cooperation and collaboration of the parties, structural impediments to equal pay could be eradicated. We can work together to build an inclusive, diverse academic environment that values the contributions of everyone and provides opportunities for all to reach their full potential. Let this call to action inspire policymakers, institutions, and individuals alike to champion meaningful reforms and create a fairer future for all.

Conclusion

The gender pay gap is an issue in academia and beyond that requires a comprehensive, multi-faceted approach.3 The evidence speaks for itself: those countries that have enacted pay transparency policies reinforced institutional frameworks and encouraged cultural and workforce adaptations have achieved quantifiable success in narrowing this gap. Emboldened by these examples of success, we must now act decisively to ensure a level playing field for all.

Policymakers have a central role to play in implementing comprehensive pay transparency legislation. Cross-firm pay transparency, as experienced in Slovakia, offers a tested model toward increasing the floor of wages while generating fairness. Besides that, gender equity audits should be institutionalized to identify systemic disparities and implement targeted corrective measures. These audits must include intersectional frameworks that allow for addressing the compounded inequities faced by women of color, LGBTQ+, and other marginalized groups.

These are changes academia needs to implement, from transparent pay structures to fair promotions based on merit. Every institution should be well equipped with support systems for women, such as mentorship programs, negotiation training, and leadership development, to help eliminate the barriers that prevent women from advancing. By giving precedence to these measures, institutions can take the lead in bringing inclusivity and equity into reality.

The power to cause systemic change in unions and advocacy groups can be affected. Empower unions to negotiate for pay equity policies, and facilitate collective bargaining to institutionalize fairness. These groups also have to make the struggles of underrepresented groups heard, too.

Ultimately, society needs to question the cultural attitudes that undervalue women's work and foster systemic biases. It is the changing perceptions and fostering inclusivity at every level—government, institutions, and communities—that lays the foundation for lasting change.

Now is the time for action. These focused approaches will help bring down the structural barriers to maintaining the gender pay gap if taken up and acted upon collaboratively. Let us work together to create a diverse, inclusive, and equitable academic environment where everyone's contribution is valued, and opportunities for success are equally assured. May this call to action ring loud and clear, stirring the souls of policymakers, institutions, and individuals toward meaningful reform and a fairer future for all.